As artificial intelligence becomes more adept at generating realistic images and videos, the threat of deepfakes has become one of the most pressing challenges in digital media today. Governments, social media platforms, and AI developers have turned to invisible watermarks as a potential solution—embedding undetectable signals in images to identify AI-generated content. But a groundbreaking study from the University of Waterloo shows that these protective measures may be far less reliable than we hoped.

Watermarks Can Be Stripped Without Any Knowledge of Their Design

The research, conducted by the Cybersecurity and Privacy Institute at the University of Waterloo, introduces a tool called UnMarker, capable of removing both traditional and semantic watermarks from AI-generated images. What makes UnMarker especially alarming is its efficiency and universality: it doesn’t require any knowledge of how the watermark was created, what algorithm was used, or even whether a watermark exists in the image.

According to the lead researcher, Andre Kassis, the implications are severe. “From political smear campaigns to non-consensual explicit content, the misuse of AI can have devastating effects if we can’t distinguish what’s real from what’s fake,” he warned.

UnMarker Targets the Image’s Spectral Domain

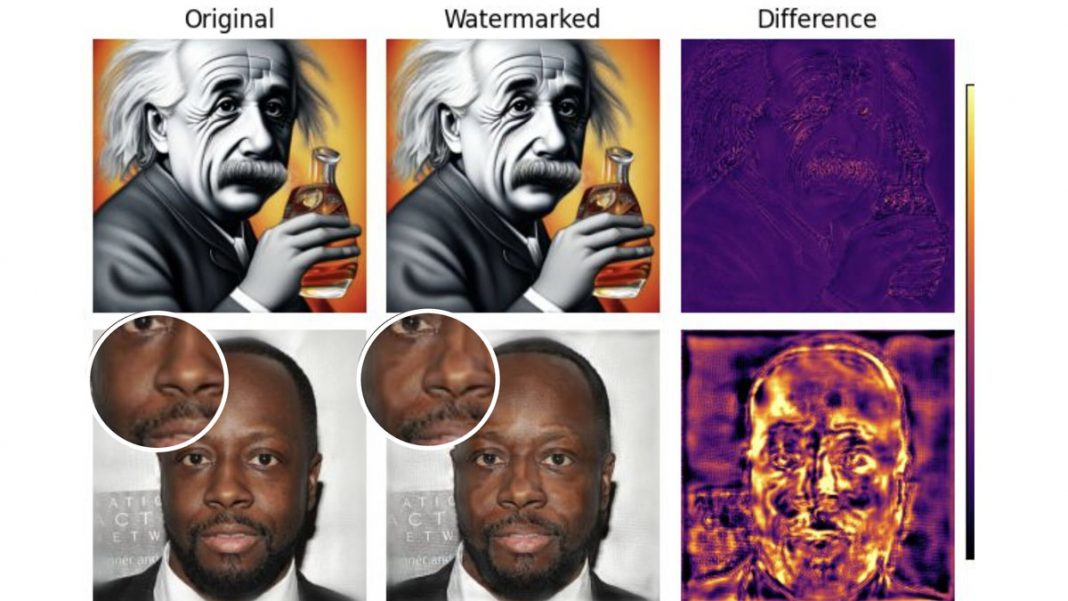

The study reveals that most invisible watermarks function by subtly altering the spectral domain of an image—this means tweaking the patterns of pixel intensity across different spatial frequencies. These modifications are hidden from the human eye but can be detected by specialized tools.

UnMarker cleverly identifies statistical anomalies in the pixel frequencies and neutralizes them, rendering the watermark unreadable while leaving the image visually unchanged. In tests, UnMarker succeeded in over 50% of cases against some of the industry’s leading watermark systems, including Google’s SynthID and Meta’s Stable Signature.

AI Companies Under Pressure

AI leaders like OpenAI, Google, and Meta have promoted watermarking as a cornerstone of responsible AI deployment. These watermarks are designed to be invisible and robust, surviving common transformations like resizing, cropping, or compression. But the Waterloo study demonstrates that even the best-designed systems are vulnerable to automated attacks.

Dr. Urs Hengartner, co-author of the study, emphasized how the dual requirements for watermarks—invisibility and resilience—create inherent limitations in their design, making them easier to exploit. “Once we understood this tradeoff,” he said, “developing a general-purpose attack became a matter of targeting the image’s structure.”

A Wake-Up Call for Policymakers and Tech Companies

The study’s findings raise urgent questions about the future of AI content verification. As deepfakes evolve, relying on fragile watermarking systems may offer a false sense of security. If researchers with ethical intentions can bypass these systems, so can malicious actors—potentially unleashing fake images and videos that deceive the public, undermine trust in institutions, or incite violence.

Policymakers pushing for AI labeling laws may need to look beyond watermarking to develop more robust safeguards, including cryptographic signatures, blockchain-backed authenticity logs, and platform-level detection systems that combine multiple indicators of manipulation.

Conclusion: Deepfakes Still Pose a Serious Threat

The University of Waterloo’s research serves as a critical reminder that watermarking alone cannot protect us from the risks posed by deepfakes. As the line between real and fake content continues to blur, both technical and policy-based solutions must evolve rapidly. Until then, users should remain skeptical and vigilant—because in the digital age, seeing is no longer believing.