A team of Japanese researchers from NTT Communication Science Laboratories has developed a groundbreaking method that allows artificial intelligence (AI) to translate brain scans into textual descriptions of human thoughts and mental imagery. Led by Tomoyasu Horikawa, this innovative approach combines advanced neuroimaging with language models, bringing science one step closer to decoding how the human brain forms and processes meaning.

The new AI system doesn’t literally “read minds,” but it represents a major leap forward in understanding how neural patterns correspond to semantic information. The researchers trained the model using brain activity recorded through functional MRI (fMRI) while six volunteers watched over 2,000 short, soundless videos featuring everything from playful animals to emotional animations and daily life scenes. Each clip lasted only a few seconds, yet together they formed a massive dataset showing how the brain reacts to visual experiences.

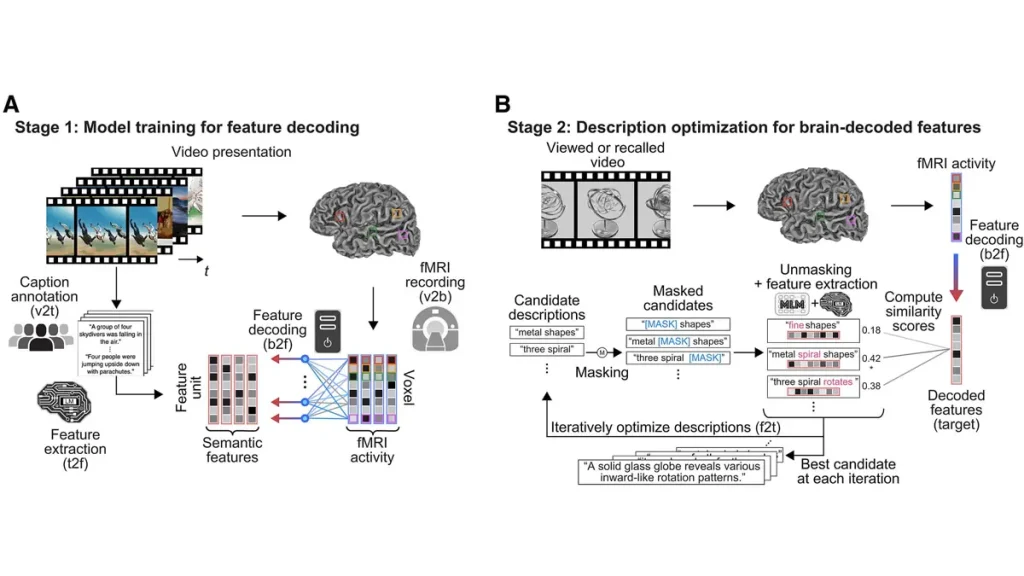

To teach the AI what these brain patterns meant, each video was paired with 20 subtitles written by online participants, which described what was happening in the clips. These captions were cleaned and standardized using ChatGPT, then converted into semantic vectors—mathematical representations of meaning—using DeBERTa, a large-scale language model. The researchers then mapped these semantic vectors to the volunteers’ brain activity, essentially training the AI to recognize which regions of the brain activate in response to specific types of meaning.

Instead of relying on opaque deep learning systems, Horikawa’s team used a transparent linear model, allowing scientists to visualize which brain areas correspond to particular aspects of semantic information. Once the model learned how to predict “content vectors” from observed brain activity, it used another AI, RoBERTa, to iteratively generate text descriptions. Through more than a hundred refinement steps, the system gradually replaced placeholder words until the sentences accurately captured what the participants were seeing—or later, recalling.

At first, the generated phrases were nonsensical. But with each iteration, the text became more coherent, culminating in fully structured descriptions that often matched the original videos. Remarkably, the AI correctly associated videos with their corresponding generated captions in about half of all cases, even when faced with 100 possible options. When researchers altered the word order in generated text, accuracy dropped sharply, showing that the model wasn’t just picking keywords but was grasping deeper relational meaning between objects, actions, and contexts.

Perhaps the most astonishing finding came when participants were asked to recall videos instead of watching them. The same model—trained only on visual perception—was able to generate accurate textual descriptions of recalled scenes. This discovery suggests that the brain uses similar neural representations for seeing and remembering, and that these can be decoded into language even without activating traditional “speech areas.” When those language-processing regions were intentionally excluded from analysis, the AI still produced coherent text, indicating that semantic understanding is distributed throughout the brain, not localized in specific zones.

The implications of this research are profound. Such technology could one day help people who have lost the ability to speak, such as those with aphasia or neurodegenerative diseases, to communicate through nonverbal brain activity. However, the researchers emphasize that this is not a mind-reading device. It requires personalized brain data, extensive fMRI sessions, and a narrowly defined set of visual stimuli. The results also depend heavily on the language models and training data, meaning different systems could produce very different interpretations.

Conclusion: While the technology is still in its early stages, this research marks a transformative step toward understanding how AI can interpret human thought patterns. By bridging neuroscience and machine learning, Japanese scientists have opened new possibilities for communication, cognition, and the future of human–AI interfaces.