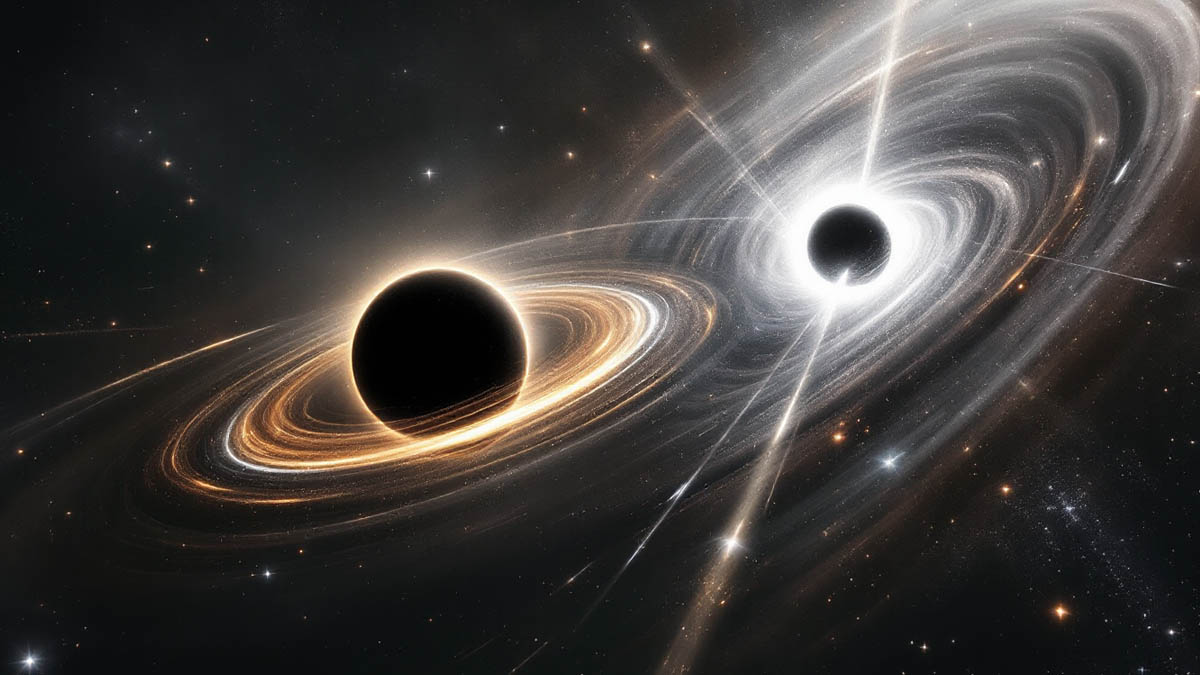

In a groundbreaking discovery, Finnish astronomers from the University of Turku have released the first-ever image of two black holes orbiting each other, marking a monumental milestone in astrophysics. This cosmic duo, located nearly five billion light-years from Earth, showcases an extraordinary system where two supermassive black holes are locked in a 12-year orbital cycle — a true waltz of gravity and light across the universe.

The discovery was made possible through the detection of subtle oscillations in radio waves observed by both ground-based and space telescopes. The larger black hole, which forms the blazar OJ287, is an enormous entity estimated to be 18 billion times more massive than the Sun. The smaller black hole is surrounded by a stream of high-energy particles moving at speeds close to that of light. According to lead astronomer Mauri Valtonen, this is the first time scientists have successfully captured a visual representation of both black holes in such a system. “The black holes themselves are completely dark,” he explains, “but we can identify them through the powerful particle jets and the glowing gas that spirals around them.”

Black holes form when massive stars collapse under their own gravity, consuming surrounding gas, dust, stars, and even other black holes to grow larger. Around some of these cosmic giants, matter spirals inward, heats up due to friction, and emits light detectable by telescopes. These are known as active galactic nuclei, among the brightest objects in the universe. The most extreme of them are quasars — supermassive black holes billions of times heavier than the Sun that expel enormous jets of gas and radiation. When these jets are pointed directly toward Earth, they are called blazars, and OJ287 is one of the most powerful examples ever studied.

For decades, scientists suspected that OJ287 contained two black holes, but telescopes lacked the resolution needed to distinguish one from the other. The mystery traces back to the 19th century, when astronomers recorded periodic flashes of light from the region. Later studies in the 1980s proposed that these brightness variations were caused by two black holes orbiting one another, periodically blocking and enhancing each other’s emissions.

To obtain direct visual evidence, Finnish researchers turned to radio imaging data gathered from an international satellite network, including the Russian RadioAstron mission, which operated from 2011 to 2019. RadioAstron’s antenna extended halfway to the Moon, vastly improving imaging resolution and making it possible to distinguish fine details that were previously invisible. By comparing the captured radio images with theoretical models, the team identified two distinct jet sources, each corresponding to one of the black holes.

However, some uncertainty remains. The researchers caution that the two particle jets could overlap, leaving a slight chance that what appears to be two sources might, in fact, be one. Despite this, the evidence strongly supports the existence of a binary black hole system — the most direct proof yet that such gravitational pairs can be captured on camera.

Conclusion:

This historic image is more than just a scientific triumph; it’s a window into the heart of cosmic evolution. The discovery of two black holes locked in an eternal gravitational dance provides fresh insight into how galaxies grow, merge, and evolve. For the first time, humanity can witness a celestial choreography that has been unfolding for billions of years — and it’s only the beginning of what we may uncover next.